The Daily Ant hosts a weekly series, Philosophy Phridays, in which real philosophers share their thoughts at the intersection of ants and philosophy. This is the sixty-third contribution in the series, submitted by Dr. Stephen White.

“The Ant and the Grasshopper” and the Politics of Insect Responsibility

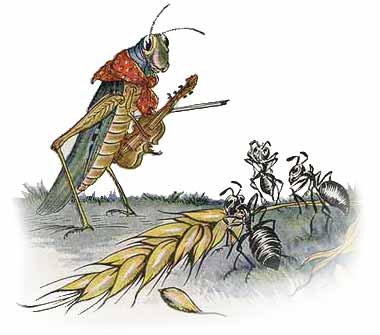

The ants of Aesop’s fable work all summer gather food to store for the winter. Meanwhile, the grasshopper plays his fiddle, having a good old time and providing some (presumably free) entertainment for the other bugs. When winter comes the grasshopper quickly runs out of food and, starving, appeals to the ants for something to eat. The ants, pointing out that they have what they have because of the work they put in over the summer, tell the grasshopper, in so many words, to fuck off.

Moralists have often taken the lesson to concern the value of prudence. One translation, available on the Library of Congress’s website, ends with the reminder that “there’s a time for work and a time for play.” But such sermonizing about sacrificing short-term pleasures for the sake of your future well-being only makes sense if the underlying political morality of the fable is taken for granted. For suppose we imagine that the grasshopper had every reason to think the ants would share their bounty with him come wintertime. Would there then be anything imprudent or irresponsible in the grasshopper’s musicmaking? To make the case that the grasshopper has behaved foolishly, we have to presuppose that he has no reasonable expectation of assistance from the ants. It is really this assumption, and the ideological framework that lies behind it, that the fable is these days most likely to evoke.

The ideology that I think “The Ant and the Grasshopper” will most readily call to mind for the modern reader is one which places an ideal of “personal responsibility” at the foundation of political morality. The line is that people need to take responsibility for their choices, and this demand for personal responsibility places constraints on what can count as an adequate scheme of distributive justice. There have, for example, been major reforms, in the last few decades, to the welfare systems in the U.S., Canada, the UK, Australia, and elsewhere, that limit the governmental assistance most people are eligible for, and have strict employment or employment-seeking requirements as conditions of assistance. The Personal Responsibility and Work Opportunity Reconciliation Act, signed into law by Bill Clinton in 1996, limits the federal welfare assistance to two years at a stretch, and five years total, with very few exceptions, in addition to requiring that recipients be actively seeking employment during the time they receive assistance. As the name of the law implies, the fundamental idea behind these requirements is that providing social assistance to people in need is basically in tension with promoting personal responsibility. To encourage a sense of personal responsibility, we need to adopt the position of Aesop’s ants: the grasshopper has made his bed, he should now starve in it.

In other words, one way to interpret the fable is to see it as expressing something like the following argument:

- The grasshopper made the choices he made, and is responsible for the consequences of those choices.

- So, if he goes hungry as a result of his lack of preparation for winter, that’s his own fault.

- Grasshoppers should suffer the negative consequences of choices for which they are responsible—or, at any rate, no one else has any moral obligation to help relieve them of these burdens, nor would a just legal order require anyone else to provide such help.

- Therefore, because the grasshopper is responsible for the position he is in, he should be left to go hungry—or, at any rate, the ants don’t have any moral obligation to provide him food, nor would a just legal order require them to do so.

The grasshopper has made his choice, and now he has to accept the consequences. On this line of argument, there is something fitting about the ants refusing the grasshopper food. They rightly punish him for his shortsightedness. Or, if that seems extreme, at least they do no wrong in refusing him food. The grasshopper has no claim on them to rescue him from his own irresponsibility. And further, reading this as a political allegory, we should likewise conclude that under a just political system, the ants would have no legal obligation to give up some of their food to save the grasshopper. Why is that, exactly? One reason that is commonly given is that a just scheme for the distribution of resources should make provision for the alleviation of disadvantages people (grasshoppers) face through no fault of their own (for example, being born into a lower socio-economic class), but not disadvantages for which they are themselves to blame.

What I wish to argue now is that the above reasoning is specious. It cannot be argued that the ants have no obligation to aid the grasshopper, who is in danger of starvation, on the grounds that he is the one to blame for the dire situation he’s in. That argument, I will try to show, is circular.

What is supposed to explain the claim that the grasshopper is responsible for the dire straits he now finds himself in? Well, he didn’t have to spend the summer playing his fiddle; and moreover, he knew, or should have known, that by choosing to spend the summer playing his fiddle rather than collecting food, he would end up with nothing to eat come winter. But notice that this result is itself partly a product of the grasshopper being denied access to food that the ants have stored away. So, what justifies blaming the grasshopper for his empty stomach, rather than the ants?

The answer, it might be said, is that the ants have no obligation to allow the grasshopper to eat the food they’ve gathered, and so the grasshopper could not have really expected to avoid starvation that way. Thus, the grasshopper really only has himself to blame. But this is where the circularity comes in. The answer to the question of why it is the grasshopper himself who is to blame for his lack of food assumes that the ants had no obligation to let the grasshopper have some of their food. But the argument above, which is supposed to show that the ants have no such obligation to aid the grasshopper, is itself premised on the claim that the grasshopper’s not having enough to eat is his own fault. Like army ants stuck in an ant mill, we’re going around in circles.

Maybe, as a way out, we should hold the grasshopper responsible for his plight on the grounds that, regardless of whether the ants are within their rights to deny him food, the grasshopper should have foreseen and taken into account that this was in fact what was likely to happen. If this is enough to establish that he is therefore responsible for the consequences of their denial, then we can get the above argument going in a way that doesn’t already assume that the conclusion is true.

But this line of reasoning is not defensible. It implies that one has no right against being treated in a certain way, so long as it was predictable that one would be treated in that way, given one’s choices. Suppose it is well-known that there is rampant sexism in a certain industry. If, despite this, a woman decides to enter this line of work, it would be morally perverse to hold that she has only herself to blame for any harassment or discrimination she experiences on the job. And it would be even more perverse to hold that she therefore has no right not to be treated in these ways.

The idea that individuals should be forced to take responsibility for the consequences of their choices is commonly appealed to in support of an ideology according to which there is little to no social responsibility on the part of the community as a whole to provide for the welfare of its members. But this ignores the fact that the consequences associated with a person’s—or, I suppose I should say, a bug’s—choices depend in all sorts of ways on the choices made by other members of the community—e.g., the ants. In order to trace the responsibility for a given outcome back to some particular insect, then, we need to rely on a prior view about what sorts of things others are entitled to do or refuse to do. And this means that ideas about the value of holding individual grasshoppers responsible for their choices can’t be used to support or oppose any particular public scheme of rights and obligations concerning the distribution of resources. Our views about distributive justice have to come first—only then can we assign responsibility to private insects.

Dr. Stephen White is an assistant professor of philosophy at Northwestern University, although this year he is visiting Princeton University as a faculty fellow at the University Center for Human Values (right next door to the University Center for Ant Values). Originally from Albuquerque, NM, Stephen considers his favorite book to be William and Emma Mackay’s classic Ants of New Mexico—despite never having read it, as it costs, like, $260. He is currently working on a project about the ethical responsibilities that individuals have when it comes to their participation in collective actions and practices.

Dr. Stephen White is an assistant professor of philosophy at Northwestern University, although this year he is visiting Princeton University as a faculty fellow at the University Center for Human Values (right next door to the University Center for Ant Values). Originally from Albuquerque, NM, Stephen considers his favorite book to be William and Emma Mackay’s classic Ants of New Mexico—despite never having read it, as it costs, like, $260. He is currently working on a project about the ethical responsibilities that individuals have when it comes to their participation in collective actions and practices.

Dr.

Dr.

Nathan Eckstrand is a Visiting Assistant Professor at

Nathan Eckstrand is a Visiting Assistant Professor at

Dr.

Dr.